Aristotle has often been mobilised in progressive causes, but nothing can be done to rehabilitate the muddled thinking of the first few chapters of his

Politics; despite acknowledging that some of his contemporaries regarded slavery as contrary to nature, he justifies it, especially in the case of Greeks enslaving non-Greeks whom they have conquered. These chapters were incessantly cited by apologists for slavery in Europe and North America, as has been superbly analysed by

Professor Sara Monoson.

And in 1772, Aristotle’s argumentation was at the centre of an

era-defining case that came before the King’s Bench in London.

James Somerset, born in West Africa, was purchased in Virginia by the merchant Charles Stewart. Stewart moved to London in 1764. He sold or leased his other slaves, but took James, then aged about 23, with him. The young man met London’s thousands-strong free Black community and white Abolitionists, and was adopted by two of them. They became his godparents when he was baptised in Holborn in 1771; shortly afterwards, he left Stewart’s service and refused to return.

Stewart, incandescent, had Somerset kidnapped and imprisoned on board a slave ship to be taken to Jamaica and sold. But Somerset’s godparents made an application for a writ of

Habeas Corpus before the King’s Bench; he was released pending the trial. The defendant, the person illegally detaining Somerset, was the ship’s captain, James Knowles.

Somerset’s legal team was financed by inveterate antislavery campaigner Granville Sharpe, one of the earliest and most assiduous Abolitionists. There was great tension in the court when the first of them, John Alleyne, rose to speak at the hearing on May 14th 1772. He introduced Aristotle into his argument almost immediately, in part using Montesquieu’s

The Spirit of Law (1748), sensing the importance of refuting the chief authority underpinning the slavers’ apologias:

’Tis well known to your Lordships, that much has been asserted by the ancient philosophers and civilians, in defence of the principles of slavery: Aristotle has particularly enlarged on that subject. An observation still it is, of one of the most able, most ingenious, most convincing writers of modern times, whom I need not hesitate, on this occasion, to prefer to Aristotle, the great Montesquieu, that Aristotle, on this subject, reasoned very unlike the philosopher. He draws his precedents from barbarous ages and nations, and then deduces maxims from them, for the contemplation and practice of civilized times and countries.Alleyne now subjected Aristotle’s prose to his lawyerly scalpel. First, if a man has spared a man in battle, whatever rule of war ensured that he did so must also make him return his liberty. Secondly, the question of a contract (Locke’s proposal) in this context is absurd, since in all contracts both sides must have full power to agree to it. If a man agrees to dispose of all rights vested in him and his descendants, he effectively stops being a moral agent and has no rights to invalidate those of his descendants. Most importantly, slavery is not natural: it is ‘a municipal relation; an institution therefore confined to certain places, aid necessarily dropt by passage, into a country where such municipal regulations do not subsist’.

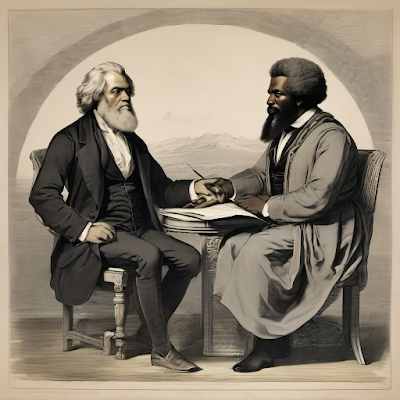

A month later, on 22 June 1772, the ruling was made in Somerset’s favour by William Murray, Lord Mansfield of Kenwood and Chief Justice of the Court of King’s Bench (Murray happened to live with a great-niece, Dido Belle, the daughter of an enslaved African woman and Mansfield’s nephew, pictured).

The public inferred that slavery was now illegal in England. This historic and public refutation of Aristotle made slave-owners across the world shudder.

England became an attractive destination for people who had escaped slavery anywhere else. And the following Saturday evening, according to the Public Advertiser, ‘near 200 Blacks…had an Entertainment at a Public-house in Westminster, to celebrate the Triumph which their Brother Somerset had obtained over Mr. Stuart his Master. Lord Mansfield’s Health was echoed round the Room; and the evening was concluded with a Ball’.

Prof Sarah Monoson and Prof Edith Hall are discussing this, and other moments when Aristotle was central to constitutional and Abolitionist debates, at the University of Chicago, on the invitation of Professor Patrice Rankine, on Thursday 4 April.